INTRODUCTION

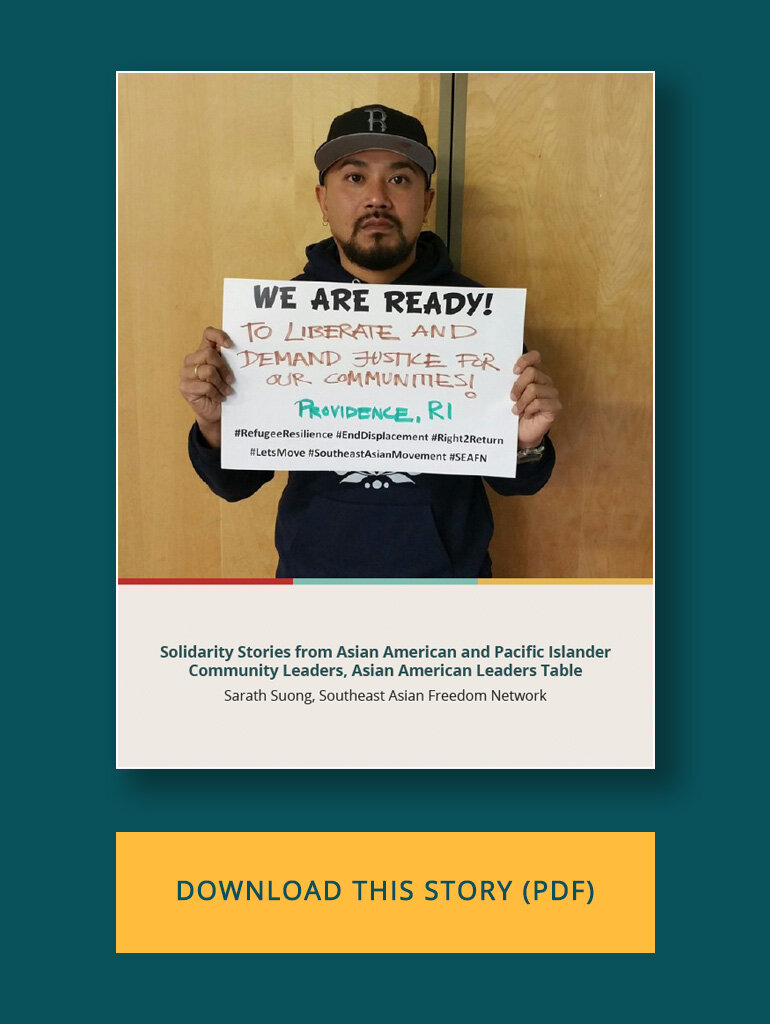

Solidarity practices have fundamentally shaped Southeast Asian Freedom Network’s (SEAFN) history and work. A national network of grassroots Southeast Asian-led organizations committed to fighting for abolition through a queer and gender justice lens, SEAFN first began organizing in response to the deportation crisis facing the Cambodian community in 2001. In this Solidarity Story, SEAFN’s national coordinator, Sarath Suong, shares the triumphs and challenges of building a national Southeast Asian movement family.

“I didn't have a queer Southeast Asian abolitionist to look up to, and so in many ways I had to create the person that I wanted to be. And so one of the things I've learned is that if there's no space that serves you, create one.”

SARATH’S KEY TAKEAWAYS

01

Solidarity requires building connections and commonalities

When Southeast Asian refugees first resettled in the United States, many built homes in places like Long Beach, Seattle, and the Twin Cities. “As we know in these big cities, you have poor and working class people, and they’re almost always Black, Brown, immigrant, and refugee, so we grew up together,” Sarath recounts. “Growing up side by side formed a really strong bond.”

Sarath learned quickly that his community and others were also being profiled and policed at disproportionate rates. “In order to survive in this racial capitalist system, many of us banded together to protect each other,” he explains. “Then they called us gangs. Then we got caught up in the 90s around the super boom of prisons, the war on drugs, more policing… we all got pulled into that.”

The 1996 antiterrorism, immigration and welfare laws, which expanded the criminal bases for deportation, affected Southeast Asians in particular, tearing families apart and deporting people to countries they did not know. In his early days of organizing anti-deportation campaigns, Sarath became aware that it would be vital to bring communities of different backgrounds together.

“In order for us to actually free our people, we have to connect with other folks who are in the struggle as well, right? Because we're not here just to make sure Southeast Asians stop getting deported and we're not in prisons anymore. We're here to make sure that the prison walls are torn down so that all of us, including Southeast Asians, are free. As a movement, we had to build those real connections with poor folks, with black folks, with brown folks, with immigrants and other refugees who are caught up in the same trappings of this racial capitalist system that we're all in together.”

02

Relationship building takes time, struggle, and joy.

In 2018, Providence Youth Student Movement (PrYSM), co-founded by Sarath, modeled an example of cross-racial solidarity. PrYSM organized with undocumented communities, Black communities, white allies, and Southeast Asians to pass one of the country’s most progressive ordinances on policing called the Community Safety Act.

“Honestly, the best thing that came out of that wasn't actually that ordinance, because law is law. We know law is not going to save us,” noted Sarath. “What was really beautiful and powerful out of all that was the coalition work that we did and the community defense structure we built.” While organizing to pass the ordinance, the coalition built a community defense program that coordinated cop watches in neighborhoods and a legal clinic program with an emphasis on addressing police brutality.

Sarath says it has taken decades of relationship and trust building to get to where SEAFN and the Southeast Asian movement space is now. That has meant not just caring for each other in moments of crisis, but sharing moments of joy and celebration as well. “Showing up for someone's graduation or baby shower is just as important as showing up for a rally or an action,” he says. “That's how you build that trust. That's how you build that community.”

03

Solidarity demands self-reflection, generative conflict, and course correction.

Throughout the Solidarity Stories we have shared, a common theme emerges about the need to build internal bridges within various Asian American groups. The same is true within the Southeast Asian community. “We call each other Southeast Asians, but there's actually real differences, real trauma, real conflicts within even the umbrella term itself,” Sarath explains. “Colorism, classism, ableism, anti-Blackness all exist within our own communities and we have to grapple with these tensions if we want to build genuine solidarity,” Sarath acknowledges.

Sarath also recognizes critiques of SEAFN that say sometimes they are too insular. “That comes from a trauma of having to always fight and scream for resources and attention,” he says. “I understand that, I see that, and I’m trying to work on it.” Sarath reminds us to always be open to building new community and connections, as well as investing in new leadership.

Some quotes in this article have been edited for clarity.

YOUR TURN

When did you first feel like you found your movement home? What memories, feelings, lessons come to mind?

Do you organize more around issues or identities? What are the nuances?

Sarath shares the experiences of resettled Southeast Asian refugees. How are these experiences different and similar from those of other Asian American communities?

How are you developing new leaders and organizers to bring into your movement space?

Video produced by Kitty Hu, Building Movement Project

Solidarity Story written by Kitty Hu